Editor’s note: In the first post in this series, Perry discussed how stories help people live by cementing social bonds, and enabling humans to see the consequences of actions through the choices of characters. In the second post, Perry described how stories can evoke strong feelings of empathy and why this occurs. Today, in the third and final post, she connects what this all means for advocates.

Written by Perry Firth, project coordinator, Seattle University’s Project on Family Homelessness and school psychology graduate student

Throughout this blog series I have covered why stories are powerful. I’ve discussed their role in human evolution, our brain’s response to good storytelling, and why and how stories facilitate empathy.

Nonprofits have used stories for decades to reach people; that stories are effective will come as no surprise to most. We know they are powerful advocacy tools. The question now is what they look like when they are used as effectively and intentionally as possible.

If you’ve been following this series, you know that effective storytelling – the kind that evokes empathy, releases oxytocin and drives action – does eight things:

- Builds tension, to keep the audience wondering what will happen next (important for transportation)

- Incorporates rich sensory details (facilitates the brain’s ability to activate as if it were experiencing the same things as the story protagonists)

- Contains characters acting in ways that highlight empathy or moral behavior (capitalizing on the brain’s natural inclination to use storytelling as a way to “try on” different decisions, also capitalizing on the behavioral mimicry described by researcher Paul Zak)

- Involves protagonists who humanize an out-group (example: stories with black children in the ’60s and ’70s, or people who are homeless today)

- Builds in easy action steps for story readers/listeners, to capitalize on their brain’s receptivity to prosocial giving, and their empathetic mental state (thanks, oxytocin!)

- Highlights stories that show how your organization has helped someone overcome adversity (Zak says the brain has a deeply rooted attraction to the basic story structure of overcoming adversity)

- Uses stories prior to fact-sharing/asking for something (money, time, action, advocacy). Sharing stories prior to making an ask means the audience’s brains will be primed for action at the story’s conclusion.

- When used to illuminate a bigger issue (e.g., world hunger), illuminates the experience of a single person who is impacted, instead of over-relying on statistics. (Statistics are important, but they are not the best at generating empathy.)

Many readers may find their organizations already doing much of this. In that case I’m confirming not what organizations should do, but why what you are doing actually works.

Using storytelling to motivate — an example

First, nonprofit communicators need to think like novelists do, says writer Sam Chisholm.

Based on his understanding of how sensory details capture attention, Chisholm gives more specific guidelines for advocates and nonprofits trying to rouse pubic action.

He says that even though nonprofits are not actual novelists, they should still employ the principles of novel-type storytelling in a limited capacity when trying to raise concern about a given issue. This doesn’t mean that facts shouldn’t be used, but that they should be interspersed with narrative.

Here’s his example, which I think is very effective. He asks the reader to consider how these two pieces of writing are different:

(Imagine that the nonprofit that wrote these two paragraphs is advocating environmental conservation.)

- Example one: There are thousands of endangered birds in our precious corner of the country. Some of the most distinctive species, species that have helped define what it means to live in New England, are perilously close to being lost forever. In fact, our recent research estimates that one species is lost every…

- Example two: When you’re walking through your neighborhood park, the soft pine needles squishing underfoot, there’s no sound that’s more arresting than the distinctive cry of the Warbler. All at once you know that you can’t possibly be anywhere but New England. Sadly, this sound, so familiar to our native North East, might soon be silenced. The Warbler is just one of thousands of species of birds…

Chisholm argues that both passages ultimately convey the same information, but the second is more effective because it capitalizes on the brain’s natural tendency to visualize — which in turn opens up the door to empathy and advocacy.

Relatedly, PowerPoint presentations that use stories actually help increase audience comprehension of key points, according to researcher Paul Zak. Not only that, the emotional engagement provided by stories actually helps the brain remember the content contained within them better than facts alone.

Lessons learned from “Humans of New York”

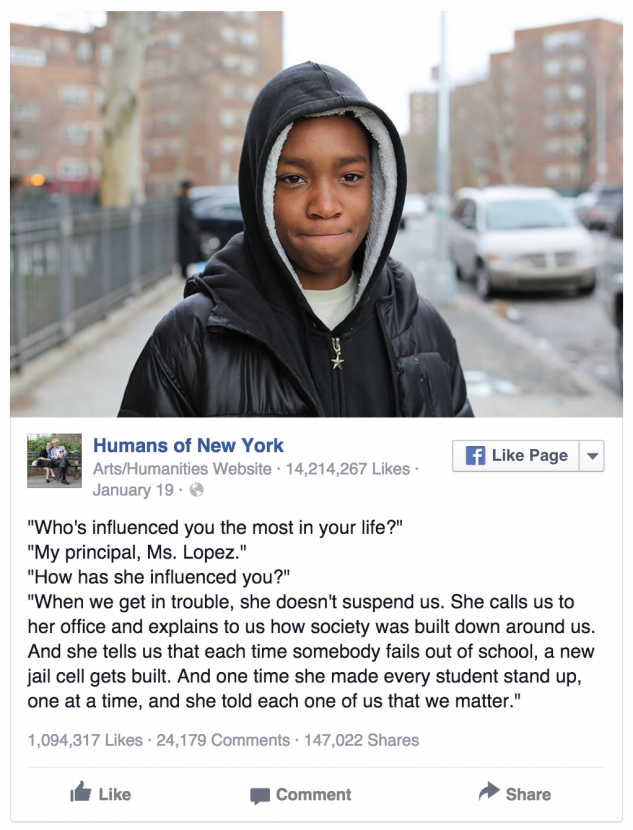

The photoblog “Humans of New York” has become a phenomenon, with more than 14 million Facebook “likes.” Analyzing why that photoblog has been so successful, Lauren Girardin with Hatch recently shared the following five “best practices” it employs:

- Embrace the human: Reduce jargon; also make a large issue understandable by exploring how it affects a single person (or family).

- Accentuate the positive: Use stories that elicit positive emotions when possible, as those are more likely to be shared.

- Track a narrative: Use the dramatic arc story structure that I discussed earlier in this series.

- Show a face: Humans have developed to pay close attention to faces, so faces are great attention grabbers.

- Do something good: Remember to connect storytelling to action steps.

Girardin says that these best practices are responsible for the blog’s success. She also credits them for the response to the “Humans of New York” story about Vidal Chastanet, the boy below. More than $1 million was raised for his school after the “Humans of New York” creator started a fundraising drive.

The suffering of one versus the suffering of thousands

What I find interesting about the example above, in which the public was motivated to give a large sum of money based on the boy’s interview, is how it exemplifies the general principle that people are more easily motivated by stories than by statistics.

The truism “one death is a tragedy, a million is a statistic” captures this tension, and also explains why stories can be better vehicles for empathy than news sources that do not use intimate human stories in their coverage.

Researchers call this “psychic numbing.” This theory explores, among other things:

- why the way information is presented shapes the emotional response of the audience, and also

- why humans distance themselves from large, overwhelming threats.

News articles or advocacy messaging that rely on statistics to generate audience empathy are actually more likely to fail than a story about how one person was deeply impacted by the advocacy issue, because statistics do not capitalize on the brain’s natural tendency to respond to storytelling.

That is, according to researchers, the reader can place themselves in the shoes of “one other, but not [the shoes] of thousands.” Hearing that large groups of people are suffering can actually cause psychological distancing, so much so that people are far more likely to help an individual than large groups of people. For instance, people give more money to charity when told about the hunger of an individual, than when told about the hunger of millions. This illustrates the general principle that people are much more likely to take action to help an individual than to help a group of statistics.

Thus, fiction can be better than news sources at generating empathy, because typically fiction describes the needs and challenges of a specific person, which the average person is hard-pressed to ignore emotionally.

Notice too, how this truth influenced generosity for the boy in the “Humans of New York” photoblog above. Every day people are told that schools are underfunded and that the public school system is in dire need of support. Millions of children fall through the cracks. Yet, after hearing the story of just one child, readers donated $1.2 million very quickly for a school in need.

All of this information on effective storytelling becomes doubly important to consider for storytelling about homelessness. Let’s face it, the human stories of homelessness are easily lost in broader cultural narratives which describe those without housing or living in extreme poverty as less human, morally bankrupt, or victims that need to be treated like children.

Storytelling homelessness

People experiencing homelessness face entrenched dehumanization and stigma. The human instinct toward in-groups and out-groups may be one reason why this occurs.

People are much more likely to feel empathy toward those they perceive to be in their tribe/community/“like them” than to those who are perceived to be outside of this limited category. In turn, people viewed to be in extreme out-groups can be dehumanized. As I wrote about in a prior post on homelessness and dehumanization, people who are homeless (in particular “visibly” and chronically homeless single adults) are in many people’s extreme out-group.

This, of course, limits empathy for those who are homeless, and therefore impedes willingness to engage with the human and structural issues that cause homelessness.

This isn’t news to Firesteel, who in a blog post titled “How Storytelling Can Help End Homelessness” made the point that stories help legislators understand how policy impacts their constituents.

Yet for all of the challenges of storytelling about homelessness, there have been successful initiatives that helped raise awareness of homelessness, and motivated action. The “Finding Our Way” storytelling project with StoryCorps is one such example.

StoryCorps

StoryCorps is the nationally renowned non-profit storytelling organization whose stories get played on National Public Radio (NPR) every Friday. If you’ve found yourself tearing up on a Friday morning after hearing a moving interview on NPR, that may have been StoryCorps.

“Finding Our Way” was a partnership with StoryCorps, Catholic Community Services of Western Washington, YWCA Seattle ǀ King ǀ Snohomish and our project. Together, we conducted nearly 100 recordings with people who have personal experience with family homelessness.

The goal was to use the StoryCorps recording platform to humanize homelessness, moving it from something that happens to others to something that can happen to people like us.

Conclusion

As someone who values beautiful writing and the art of storytelling, I’ve long been aware of the unique potential of stories to pull us toward new ways of thinking. If there is one thing that I’ve learned in the course of writing this series, it is that more than just beautiful or interesting, compelling stories are workhorses. Stories reach people even when they don’t want to be reached, and lend an unquestioned structure to our social interactions.

In a world with widening income inequality and complex problems, the ability of stories to clarify issues, cultivate our better selves, and drive meaningful action is increasingly necessary. Even as social media is used, often weakly, as a promoter of connection, it will always be the effective storyteller who fosters true interdependence. With homelessness especially, stories shed light on the humanity so often denied by our larger society.

More than just effective transporters, stories capitalize on our innate human need to feel for others. This need, to connect to others and respond to their suffering, is frequently diminished in our day-to-day life. It dies a little every time we see inequality or pain and don’t respond. Homelessness in particular challenges us to combat the story the media sells us about social structure, individual responsibility, and privilege.

So here’s to the storytellers whose stories go untold; may they get the platform they deserve. And for those of us lucky enough to hear those stories, may we respond justly.

Examples of effective storytelling

There are many other examples of effective storytelling about homelessness. Check out:

- American Refugees, an animated film project about family homelessness.

- StoryCorps “Finding Our Way” on Firesteel.

- This Firesteel blog post, “Storytelling Intersects the Personal and Political,” about how storytelling can be a political act; and this, “Whose Story Is it Anyway?,” written by my colleague Paige McAdam, analyzing the “Mean Tweets” phenomenon.

- Invisible People, Mark Horvath’s website devoted to interviewing people experiencing homelessness.

- Homeless in Seattle, the popular online community that connects stories to action.

Pingback: Empathy: What This Means For Advocacy | Just St...()

Pingback: Empathy: What This Means For Advocacy | Ideas |...()